In the television culture of my family, power failures and technical difficulties were dreaded enemies. I remember well my moments of anguish, when I was young in ‘68, sitting in the dark, unable to believe or even comprehend the sudden unplugging of my brain from the TV and the plunging of my senses into the eerie darkness and silence of a dead house. Or, when it was a glitch in the broadcast, angrily whispering “Come on! Come on! Come on!” while my ears and eyes remained fixed to the hiss and snow or to the pattern or the message, all a kind of death mask on my luminous omniarch. And as the “one moment, please” stretched into minutes, and the words and gestures of my favorite people in the whole world remained banished within the impenetrable doors of failed prime time, life itself seemed to drain away. O, what was the point of living!

Finally, when it became apparent that our ritual of furniture grasping, head shaking, gasping sighs, and name-calling proved useless, our focus turned to the only avenue of revenge available: set rejection.

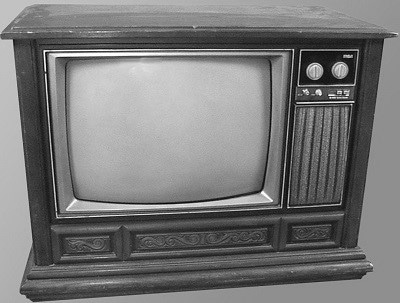

“Fine!” Dad would growl, as he stomped to the television set. “If those stupid people can’t keep their stupid show on the stupid air, we just won’t watch the stupid thing!” And with a quick flick of his fist, he’d shut off the set. (The on/off knob stuck out from the set back then, looking kind of like a rook from the game of Chess.) After which we’d mill around the house as though lost, gaze out the windows in silent agitation, and finally busy ourselves with getting ready for bed. If it was early enough in the evening, well before actual bedtime, and we really wanted to show that set a thing or two, we’d each read a book in the living room. Not a word would penetrate our minds, but just the act of holding a book in plain view of the set as punishment for its treachery was enough to give us some sense of control over the situation.

A little while into that routine, one of us would turn the TV back on, with the volume down to keep from hearing that horrible sound of static, to see if the set had learned its lesson. We did this about every thirty to sixty seconds. And when the snow or message began its slow materialization, emphasizing its complete indifference to our plight, we would again shut it off, each time with more sure and growing disgust. Then we’d all stare at our books with renewed purpose, loudly flipping pages.

Feebly, we would continually check one last time for the return of our vaudevillian master. And then, just when the world could end and we wouldn’t care, the set would finally have pity on us, and there on the glowing square appeared the light we longed to see.

We’d slap shut our books in staccato applause, drinks we had prepared for the vigil would warm or cool, Dad’s cigarette would fume the room with filter smoke, and time generally stood still while we breathlessly absorbed our dose of waking dreams.

Ah, soothing, effortless, electric sleep!

And we’d all watch without moving, heedless of rebellious bladders and unconcerned with bloodless limbs, until that dreaded (dreaded by us kids) intrusion by the redundant dimension in the form of the news woke us up. Then it was time for bed.

Occasionally, shortly after the return of power or the end of technical difficulties, after we’d immersed ourselves in prime-time euphoria, there would be a second unplugging of our brains. That was absolutely intolerable, and we’d all go ballistic.

Forgotten books thrown to the floor, hair-pulling, the calling down of fire and brimstone upon those faceless incompetents, and my father stomping to the wall while damning those idiots at the power plant or those imbeciles at the station (both mysterious references to me, then) and ripping the cord from the socket, depriving the villainously fickle creature of its lifeblood. Then we kids would sulk to bed and stare hatefully at the ceiling until real, healing sleep overcame and calmed us.

The next night we’d all watch television with tentative interest, fearing that if we allowed ourselves to be lulled, the set would again show us who was boss. We’d sit and stare askance at the screen, not willing to let it fully rejoin our family until it had proven its trustworthiness.

And so we lived, sometimes with animosity, usually with sublime admiration and often outright adoration for that peculiar member of our family, the television.

That is, until years later in Korea, when we got a taste of what entertainment was like in the old world. But that’s another tale.