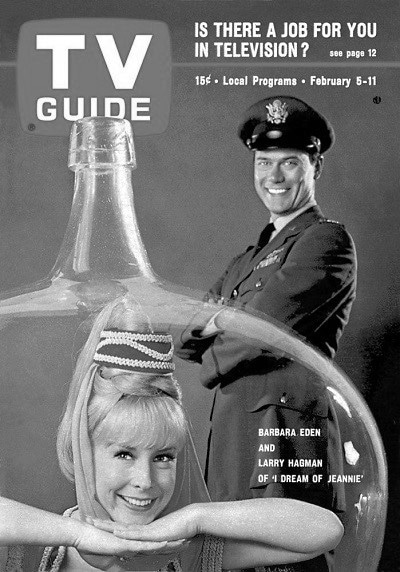

Beginning with the year I Dream of Jennie premiered, and for about three years after, when my sister took over the job for a while, I was a walking, talking TV guide. I had poor grades in math and science, passable grades in most other subjects, and was flunking history, but whenever Dad handed me that thin, stapled magazine I memorized, with one glance through its pages, every show, movie, and special on every channel for the entire week. Of course, at that time there were only the three networks, ABC, NBC, and CBS. There were also the poorly transmitted UHF channels, but we seldom watched those because there was never anything good on and it meant continually working that infernal secondary knob, the push-and-turn fine tuner. It was only out of extreme desperation that we’d make an attempt at those fuzzy, full of yak stations, so I never bothered reading them.

As Sayer of the Shows, I was indispensable to Dad, and I got great pleasure in providing him with the information, mainly because it gave me a sense of authority at home and a feeling of having a purpose in life. Memorizing the TV guide was my special ability, a talent that I alone, for a while, possessed, and therefore I was in great demand, not only by Dad but also Mom and my sister and brother as well.

Back then there was no such thing as a remote control, so an additional duty of the Sayer was to change channels. The job required no special ability, but it was still something of a privileged position. After supper Dad would sit in his chair or stretch out on the couch and have me click from one channel to another, briefly consider what was on, and then ask me about a specific show he’d seen advertised the night or week before.

I’d reply, “That doesn’t come on till tomorrow, at seven.”

“Oh. Well, what about that special—”

“Wednesday at eight.”

“And that science fiction movie—”

“Friday’s late show.”

“Okay. So what’s on tonight?”

I’d report that evening’s line up.

However, knowing what was on did not deter Dad from continuing his search for something to watch. Now and then, when there was a program coming up that he wanted to see, he’d settle for watching whatever was on the same channel. But usually, and especially on nights when there was nothing in all of primetime worth watching, he’d go from channel to channel, staying anywhere from two seconds, if the station was at commercial break, to two minutes, if something caught his attention, such as high action or drama or a favorite actor. And I got pretty good at anticipating his commands, having linked keywords to specific channels:

“Go to—” I’d turn to five.

Dad would study the screen for a moment, his jaw firmly set, his eyes unblinking, with just a touch of frown between his brows.

“Let’s try—” In one blurp of clicks I’d shoot to twelve.

“Don’t switch so fast. You’ll wear out the knob.”

And that was really the only aspect of my job as Changer that was bothersome. Switching from four to five was no problem, but that long trek to twelve was always a drag.

Again my father would briefly scrutinize what was on.

“Go back—” Slowly, agonizingly, I’d turn the knob back to four, click…click…click, like the second hand of a clock. And while those seconds may not seem very long while pursuing some vigorous activity, it becomes a slice of near forever when you’re waiting for something to happen.

“Go to—” I’d turn back to five.

“Let’s try….”

I’ve always wondered, why couldn’t the channels be four, five, and six?