At the request of Commissioner John Allocco, Dr. Michelle Sivilich, Executive Director of Save Crystal River, Inc., provided the Board of County Commissioners with a presentation regarding the Kings Bay Restoration Project on Feb. 25, 2020. Dr. Sivilich discussed the processes used and the efforts of the pilot restoration project, which entails the last five years.

The presentation provided the board with detailed information which may be used in planning future approaches to restoring Hernando County waterways that are in trouble.

Save Crystal River is a 501c3 not for profit organization of local citizens dedicated to preserving Florida’s waters. Save Crystal River is in its 50th year of restoration. Sivilich was joined by Jim Anderson, the founder of Sea and Shoreline, which is a partner in this project.

The approach used by Save Crystal River was outlined in five goals:

- Remove invasive Lyngbya and years of accumulated detrital material, commonly known as “muck.”

- Replant native eelgrass that can outcompete the algae for nutrients and add oxygen to the waters

- Protect and maintain the newly planted grasses

- Prevent ongoing introduction of pollutants (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, runoff) that contribute to algae growth & water degradation

- Educate others regarding the mission of the organization and how everyone in the community can help restore the waterway.

Waterways restored so far

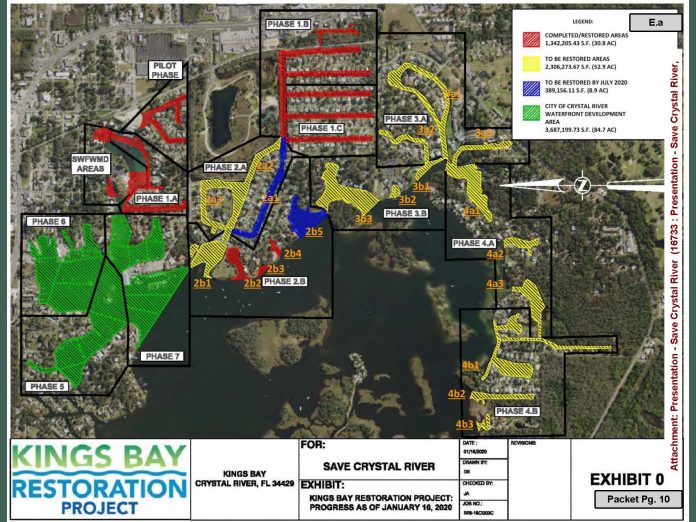

The subject of the restoration project is in Crystal River near the Three Sister Springs area. The project is focusing on inland areas and canals which link to Kings Bay and Crystal River. The recently completed project is at the northeast end of Kings Bay and directly north of Three Sister Springs.

An area was added later, west of Three Sisters, which included the cleanup of upland residential canals between private properties. Because it has been observed in the past in Weeki Wachee, Commissioner Wayne Dukes asked Sivilich if the clearing of those canals will have unintended consequences of “sucking more muck into the river.”

Sivilich explained that unlike dredging, the methods used by Sea and Shoreline will prevent that.

Future projects are planned for nearly all areas on the eastside of Kings Bay and connecting inland canals.

Removal of muck and invasive flora

Lyngbya is a cyanobacterium (blue-green alga), forming long filaments inside a rigid sheath with a slimy surface. The sheaths collect and form large “mats” on the floor of the waterway. Not only is Lyngbya invasive and unpleasant to touch, it can also cause skin reactions in humans.

Sea and Shoreline is responsible for the removal of the muck, using a hydraulic vacuum. “Just like vacuuming your carpet.” Sivilich said, “We’re not deepening the canals.” With the muck cleared, certified divers hand-vacuum Lyngbya, which is then pumped back to a dewatering site.

On it’s way to the dewatering site, the vacuumed contents are passed through a giant screen, which collects cell phones, keys and other items lost by humans.

At the dewatering site, large, flexible, bag-like apparati called geotubes separate all the Lyngbya particles and other pollutants from the water. Inside the geotubes, the water to be cleaned is introduced to a special polymer to bind the solid particles. The freshly cleaned water is then returned to the waterway.

What’s left behind is clumps of nitrogen and phosphorus-containing fertilizer, which is shipped to a local cow farm.

“Rockstar Eelgrass”

“So much like farming on land, this is farming underwater, so we’ve prepared our field. We have that nice bed of sand then we start planting…”

After the area is cleared of Lyngbya, new eelgrass is planted. This isn’t your average eelgrass, this is “Rockstar Eelgrass,” engineered for fast growth by a UF scientist. Rockstar also sends out runners that will extend 7 feet in all directions. For the first year, the eelgrass is kept in “exclusion devices,” or manatee-friendly cages to protect the grass during its root establishment and initial growth. Once a month, the cages are cleaned by divers.

The eelgrass is beneficial to the waterway because it produces oxygen, which is obviously good for the life of the waterway and its ecosystem, but also because it helps to keep Lyngbya out. Eelgrass is a favorite snack for manatees when they congregate in the winter.

Sivilich reported that the project has received approximately $18.6 million in state-funded grants, donations and fundraising proceeds. To date, 30.8 acres have been restored with 130,000 eelgrass plants planted after the removal of over 200-million pounds of Lyngbya and detrital material. The efforts have resulted in a 95% reduction of phosphorus and a 50% reduction of nitrogen pollution.

She estimated that the completed areas cost between $300-500,000 per half-acre, but cautioned that different areas require different approaches, and the prices could vary.

Evidence of the project’s success is seen in the return of manatees in the winter along with other marine life. “We’re seeing an increase – every kind of species. We’re seeing bedding bass for the first time in decades, we’re seeing crayfish, blue crabs, everything is coming back in not just freshwater species, but marine species also come in and and breed in these upland spring canals so lots of animal utilization.”

Unclogging of spring vents

Springs feed the river through vents and “boils” on the King’s Bay floor. The removal of harmful debris has resulted in the unclogging of over 400 vents, resulting in more water flowing into the river, which dilutes more phosphorus and nitrogen and provides more rest areas for manatees. It will also increase the flow of the spring, which will keep undesired materials from washing back in.

Sivilich reported that one spring vent was found under 11 feet of muck.

Preserving the Eelgrass

Sivilich reported that anchoring of vessels, as well as propeller scarring is the biggest threat to seagrasses. In addition to being watchful for eelgrass while boating, it’s recommended to anchor in areas without eelgrass, and use a hydraulic anchor, Power-Pole ® or home-made “spud” or small-footprint anchor. A mushroom style anchor is preferred over a Danforth style.

Allocco commented at the end of the presentation that “There’s no such ‘silver bullet’ to protect the springs (in Hernando county). We’re going to need a multi-faceted approach.” Allocco stated that residents have reported the Weeki Wachee river flowing more slowly over the years, and questioned if “muck” could be clogging vents in the springs that feed it.

“Just eliminating septic isn’t going to be the answer.”

The board will continue to discuss options for funding and strategy for restoration efforts.