By Terry Dunne

Special to Hernando Sun

On our old black and white TV, my big brother and I’d stay up late watching Marine Corps combat movies. Nothing so inspired as John Wayne in Sands of Iwo Jima. No one was as tough as Frank Lovejoy in Retreat Hell. And there was nothing nobler, to us, than two brothers serving together in combat.

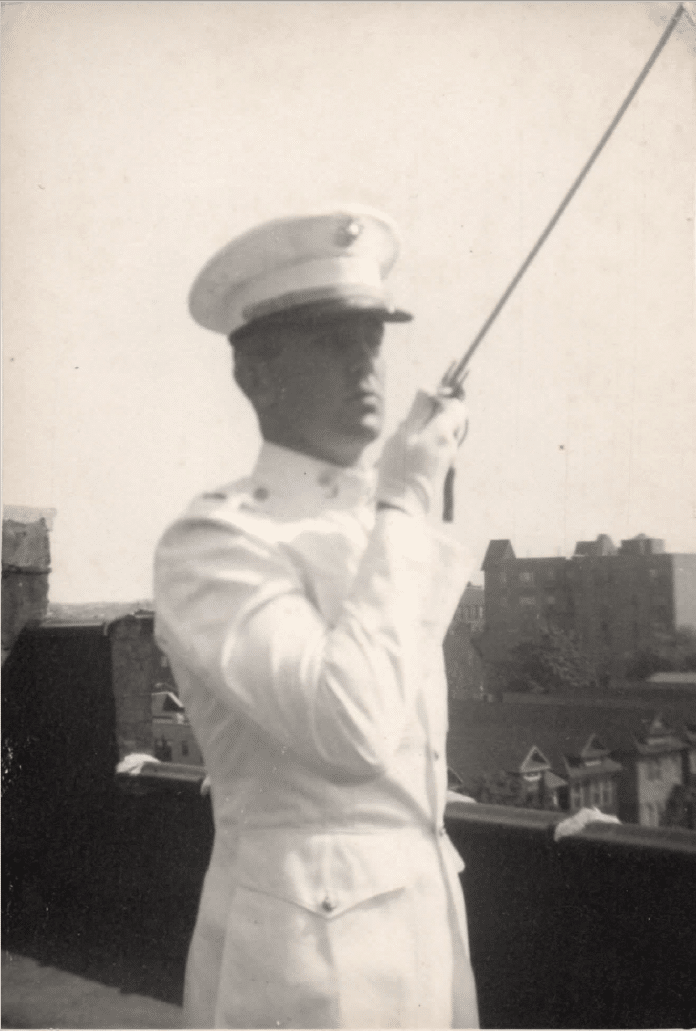

The Mameluke Sword, the U.S. Marine Corps officer’s sword of Tripoli fame, was presented to my brother, 2nd Lt. Eddie Dunne, in 1961. It was a beautiful thing that seemed to sparkle with virtue. As he pulled it from its scabbard, he spoke of honor and courage, of devotion to duty, and of the noble citizen-soldier willing to go to the far reaches of the earth to defend his country. The sword sparkled all the more. We were New York City Irish, second-generation American, and when my brother finished his oration, he slammed his beer on the bar and said with conviction, “There’s nobody tougher than the Irish.”

I followed Eddie into the Marine Corps and we wound up together in the Caribbean, afloat aboard the helicopter carrier U.S.S. Guadalcanal. When we got back to the states, in June, ’66, Eddie’s time was up and his second son had been born.

He took a job with IBM and I received orders to WestPac (Vietnam). In the meantime, the electric news broke that Robert O’Malley, fellow New York City Irishman one neighborhood over, had won the Medal of Honor in Vietnam. We were psyched.

It didn’t take long to get hit in Vietnam. A booby-trapped hand grenade peppered me with shrapnel but I was OK and returned to duty after a week in the hospital. However, Marines in dress blues and serious faces had visited my mom and the news had shaken my brother. Against all advice, he ditched his career and signed up for Vietnam. He arrived in 1968, just in time for the Tet offensive.

But he was somebody now. He was infantry Captain Edward Francis Dunne, packing six machine guns, three mortars, six rocket launchers, and 100-or-so crack shot Marine riflemen. He helped bloody the North Vietnamese Army during the 1968 retake of Hue City and, years later at his rifle company’s reunions, stories of courage and valor reflected well on his conduct during that time of heavy combat.

I got back to Vietnam midway through my brother’s tour and we served together in the 3rd Bn, 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division. In the lovely Que Son Valley hill country west of Da Nang, elements of the 1st Marine Division took on the rough and tumble 2nd NVA Division and, for a short time, Eddie and I lived our youthful fantasies, he a rifle company commander, me a rifle company platoon sergeant. The Marine Corps caught up with us—something about the Sullivan brothers—so we signed waivers to stay in-country and that was that.

It was after we returned home to the states that it happened. On a Sunday morning under the sun-dappled girders of the #7 subway line in New York City’s Woodside neighborhood, we were walking to St. Sebastian’s Church when a neighborhood kid we knew confronted us. It was about the war and this fired-up little hophead actually spit at my brother. Eddie, resplendent in officer dress blues, wife and two little boys in tow, was open-mouthed astounded. How could such cruel derision be? Like most Vietnam veterans, he had no way of defending himself, no way at all. He shrunk within.

The years went by. The sword tarnished, its glimmer of virtue vanishing. Divorce came. Then another. At a wedding, a man asked my brother, “How could you fight for something you didn’t believe in?” Assault charges were filed. One of Eddie’s sons married into another Irish family and the new in-laws preferred not to associate with us baby killers. Hard living had declined Eddie’s health and he was hunched over when we walked into a new generation Irish bar in New York City’s Maspeth neighborhood. The young Irish bartender, polished and stern, took one look at my brother and with a heavy brogue said, “Sir, I cannot serve you.”

Some years later when I visited Eddie in North Carolina, the sword was on the wall, its handle broken, the scabbard dirty. Then the aneurysm came and Eddie was committed to the North Carolina State Veterans Home in Fayetteville, NC.

I’d drive up from Florida to visit him, pack him into a wheelchair, and take him to the downtown Fayetteville street mall for lunch and cocktails. On our last Memorial Day together, we watched the city of Fayetteville’s Memorial Day Parade.

It was cold for Fayetteville and, to keep my brother warm in the wheelchair, I wrapped a camouflage poncho liner around his shoulders. As the parade went by, a high school marching band appeared, with a big American flag in front. Eddie saw it, wanted to stand up and salute, but couldn’t make it out of the wheelchair.

Then, tender mercies. As the marching band came abreast, stopped, and marked time in place to the rat-a-tat-tat of the drums, the Drum Major pointed his baton at my brother’s creaky efforts and Eddie strengthened. Four Majorettes, smiling young high school girls, turned, stepped up, and faced my brother with twirling batons, nodding at him in salute. He strengthened more, tried to get all the way up, but couldn’t make it. The poncho liner slipped from his shoulder.

One of the majorettes stopped, stepped toward my brother, and pulled the poncho liner close around his neck. With a musical southern accent, this lovely young woman said, “God Bless you, Marine.” Somehow Eddie made it all the way up as he snapped a smart Marine officer’s salute.

Seeing my brother momentarily tall and straight, knowing what I knew about his honorable combat service, and understanding how he’d been treated by his fellow American citizens, I couldn’t help but think, “There’s nobody tougher than the Americans.”