How far would you go for your dream? Would you walk for miles to a school to get an education? Would you travel to another continent for the opportunity to pursue what you loved the most? Would you come back home and stand up for your beliefs? Would you be a role model for others of your race? Bessie Coleman, American aviator, did all of that for her dream. On February 14, the US Mint honored Coleman by making her the sixth woman to be a part of the American Women Series Quarters.

Elizabeth (Bessie) Coleman was born on January 26, 1892 in Atlanta,Texas. It’s a small town that’s situated on the very eastern side of the state. Bessie’s mother, Susan, was African American and worked as a maid. Her father, George, was a sharecropper, and he was African American and part Native American; his ancestors were Choctaw. Bessie was the tenth child in a family of 13 children.

By age six, Bessie walked four miles each day to a segregated one-room schoolhouse. She loved reading, and was exceptionally good at math. At age 12, she received a scholarship to Missionary Baptist Church School. During each year, schooling stopped for the cotton harvest and the Coleman children were required to pick cotton. Their mother also did others’ laundry to earn extra income.

At age 18, Bessie used her entire savings to attend one semester of college where she went to what is today’s Langston University. She was forced to drop out of class when there wasn’t enough money to continue.

In 1915, Bessie went to live with some of her brothers in Chicago. Here, she attended beauty school and became a manicurist at the White Sox Barber Shop. It was probably there that she first heard the stories told by WWI pilots. She heard tales about French women flying airplanes and becoming pilots, she heard about adventures and faraway places. Her brothers teased her that she was missing out. Those stories stirred something in her; she wanted to fly!

Bessie worked two jobs in 1920 and wanted to be a pilot. However, it was impossible for her to get accepted into American flight schools as at the time, it was a man’s world and they were not admitting women or people of color.

Her dream seemed to be on hold until newspaper Publisher Robert Abbott stepped in. He ran the African American newspaper called the Chicago Defender and devoted some news space to her quest. This caught the eye of banker and businessman Jesse Binga. He was a man who landed in Chicago with just $10 in his pocket, so he definitely knew what it was like to be in need. The banker and the publisher soon joined forces to help Bessie achieve her dream. They encouraged her to learn French, travel to France and get her pilot’s license there. Bessie left for Paris in November 1920, and within seven months she became a pilot.

Bessie Coleman became the first African American woman and first Native American person to earn an aviator’s pilot license. She earned her international pilot’s license in France on June 15, 1921. She was also the first African American woman and Native American woman to do so as well! She was in Europe for two months to complete extensive flight training, The newspapers of September 1921, say she left the United States as a manicurist and returned as an aviatrix. Though she is recognized as the first licensed woman pilot in the United States, Bessie Coleman is an unfamiliar name to many of us. Maybe we remember someone else; another aviatrix by the name of Amelia Earhart, who had her first pilot’s license issued two years later on May 16, 1923.

Even with a license, the early pilots didn’t have many opportunities to earn a regular income. Regular commercial flights were years away, so Bessie decided to learn stunt flying! In early 1922, she returned to Europe for two months of rigorous training. She also had hopes of buying her own plane and starting her own flight school one day! More dreams!

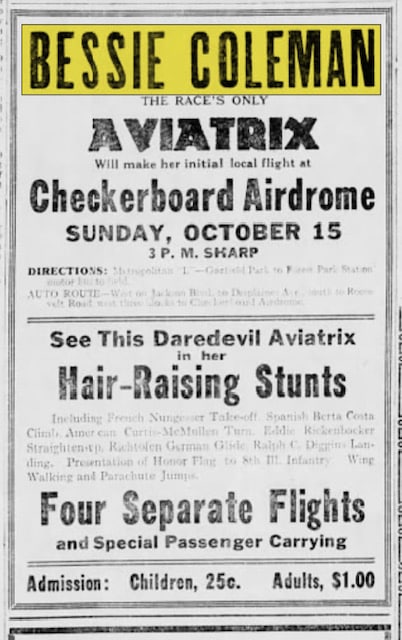

From 1922-1926, Bessie Coleman became an aviator daredevil. She performed around the United States in shows and fairs, but always remembered to come back to her “home folks” in Chicago.

Stunt flying of the 1920s was wild, exciting and dangerous; it was called “barnstorming.” The fearless flyers often used a farmer’s pasture and barn as the site of an improvised air show. Bessie took “edge of your seat” chances, earning her nicknames like Brave Bessie and Queen Bess. She was famous for doing “loop-the-loops,” taking her plane in figure eights and wing-walking. She has even parachuted from the wing!

Her United States air performance on September 3, 1922 was the first public flight by an African American woman. She achieved her dream of purchasing her own plane in the early 1920s. In 1923, Bessie was fortunate enough to survive a major airplane accident. She suffered a broken leg and cracked ribs when her plane stalled and crashed.

Bessie continued to fly even after this. She was famous in Europe and the United States. She flew exhibitions, gave speeches and showed films of her acrobatics. As she toured, Bessie fought for acceptance and equality. She refused to speak anywhere where people were segregated or discriminated against. In 1925, she agreed to perform an air show only after they made a single stadium entrance, not two separate ones according to the color of your skin.

Bessie was just 34 years old when a tragic accident took her life on the morning of April 30, 1926. She perished while taking a test flight with mechanic William Wills. They were going up to look over the Jacksonville area for the next air show. I imagine it was something they’d done dozens of other times before, nothing special. However, at 3,000 feet something went terribly wrong, a loose wrench got stuck in the engine and Wills couldn’t control the steering. The open-style plane dropped altitude and flipped over. Bessie was unfortunately not wearing her seat belt. She fell several hundred feet and did not survive. William Wills struggled with the plane and he too, lost his life as the aircraft crashed to the ground and caught fire.

It was a sad day for aviation. Her adopted family in Orlando, Florida arranged a memorial service for her at her favorite church, Mt. Zion Baptist. So many people came! Bessie was remembered for her accomplishments, but also for her faith, her discipline and for the example she displayed for young women everywhere. Her body was taken by train to her other “home” in Illinois. At least ten thousand people paid their respects at Chicago’s Pilgrim Baptist. Very little was mentioned in the newspapers about her passing, just a few paragraphs. They mostly made note of the color of her skin – that she was African American and that her pilot mechanic, Wills, was white.

As years go by Bessie Coleman has been rightly remembered and honored. Starting in 1931, the Challenger Pilots Association of Chicago began an annual tradition of flying over her grave and dropping flowers. Many aviator clubs have been named in Bessie’s honor. She didn’t get to start her own flight school, but she has them now! Other memorials include the naming of various streets, roundabouts, libraries and schools in both the United States and Europe.

Even things not of this earth are named to honor her. In 2021, NASA named a large geographic feature (possibly a volcano) on Pluto as Coleman Mons for Bessie Coleman.

In 1995, a Bessie Coleman postage stamp was issued as part of the Black Heritage Series. This month, February 2023, she is honored by the US Mint as the sixth woman on the American Women Series Quarter. The obverse side of this shiny 25-cent coin bears her likeness. She’s dressed in full flight gear, ready for take-off, looking off into the clouds. There is a date inscribed below her name, 6.15.1921, the date she received her pilot’s license in France. It’s the date she made history for women and people of color everywhere.

Bessie Coleman certainly left this earth too soon and went out doing what she loved. There is no telling what else she would have accomplished if her life had not ended so soon. She is remembered fondly everywhere from Paris to Munich to Amsterdam. She is remembered across the United States in cities from Orlando to Chicago and all the places in between! She opened many, many doors for others to explore aviation. Just think of the Tuskegee Airmen of WWII. Without her, maybe there would be no them.

“The air is the only place free from prejudice.” ….Bessie Coleman.