Jan. 27 was International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Although the number of Holocaust survivors is dwindling each year, the memory of that dark period in history is alive in the friends and descendants of the tens of millions of people who were either killed or survived that period.

Roslyn Franken

Local author Roslyn Franken’s mother, Sonja, was a Holocaust survivor. She tells the incredible stories of her mother and father in her book, “Meant to Be.” Roslyn also delivers presentations throughout Florida, the United States, Canada and Europe relating her parents’ survival and triumph over death.

Her mother grew up in the Netherlands and was raised in a traditional Jewish family. When the Nazis took over her country, Sonja, who was only fifteen at the time, watched her parents, two brothers and eldest sister taken away and never saw them again. She was in eleven concentration camps where she was forced to live and work as a slave laborer in the most horrendous of conditions, experiencing starvation, malnutrition, and infectious diseases. Sonja faced death in the gas chambers three times, but through her wits and innumerable miracles, she survived it all and went on to live a long, productive life.

Last year, Roslyn gave talks at four high schools and one Rotary Club in the area of Vught where the first concentration camp in which Sonja was imprisoned was located. This was before her mother was sent to Auschwitz. Roslyn visited the Camp Vught Memorial and Museum.

“There are no words to describe the depth of emotions I experienced being there, seeing the barracks she would have slept in, seeing the crematorium that burned so many bodies of innocent people,” Roslyn remarks.

“Her [Sonja’s] traumatic experiences gave her an appreciation for life, love, freedom, and peace,” Roslyn continues.

They also gave her the resilience and fortitude to overcome obstacles later in life. Amazingly enough, Sonja displayed two other characteristics: a positive attitude and a sense of humor.

Roslyn recounts that when her mother was 56, she was diagnosed with Stage Four cancer. The doctors gave her only two years to live with the strongest chemotherapy available at the time. She refused to accept that prognosis and told the doctors, “Hitler didn’t get me; my cancer won’t get me. I have too much to live for.”

Dave Rogoff

Dave Rogoff has a somewhat different Holocaust story. He was born in New Jersey in 1949 after World War II was over, so he didn’t experience the atrocities directly, but it still affected him.

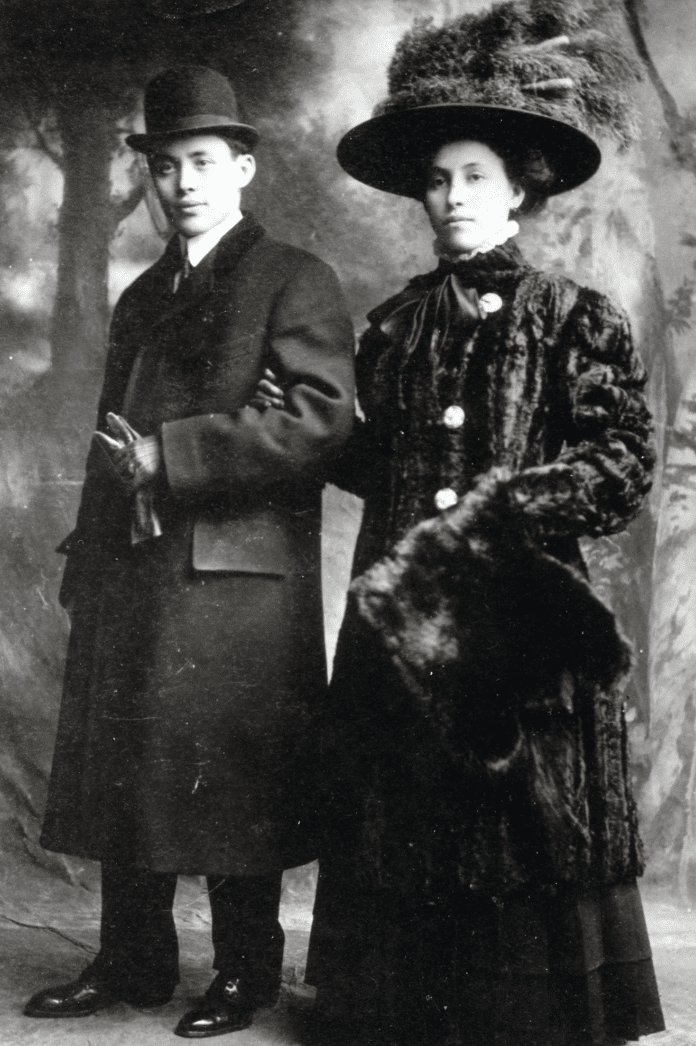

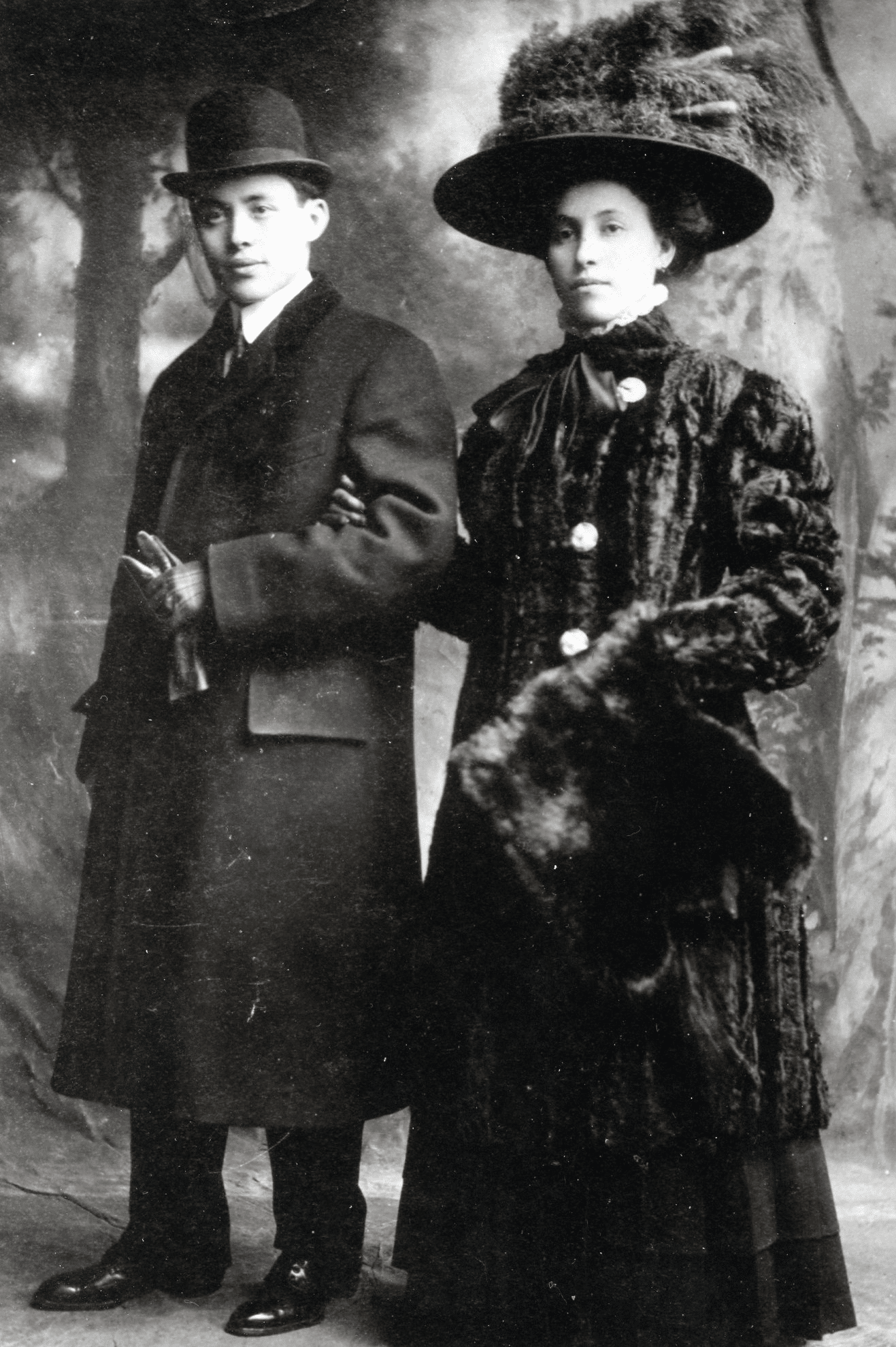

His ancestors came from Lithuania, which at that time was a part of Poland. His grandmother, Lena, and her brother, Fyvel Dovid, emigrated to the United States before the atrocities began.

Fyvel went back to get his family and was never heard from again. However, his daughter was smuggled out by a Polish Catholic family by posing as their deaf-mute maid. She went to Israel after the war.

Dave’s father spoke about his cousin, whom they called by a nickname, “Hanka.” After moving to Israel, she married and had children. Dave met her son, Shalom, when he visited Israel, but he never said much about his mother and neither did Shalom’s son, Fyvel Dovid, who was named after his grandfather. It was, perhaps, because the memories were too painful for Hanka to talk about.

The Wald Family

Max Wald, whose sister, Rosalie, attends Temple Beth David in Spring Hill, is a Holocaust survivor. Rosalie was just a baby when the family fled Germany and came to the United States. However, Max, who was four at the time, remembers much of it. One experience as a young man made him realize just how fortunate he and his family were.

When he was in college, his professor showed the class some pictures depicting the gruesome experiments the Nazi doctors did on children. The thought crossed his mind that had his mother not gotten him and his eight-month-old sister out of Germany in 1939, he would have been among those children.

His story begins in 1935. The Nazis had been in power for two years. Max Wald and the Nuremberg Laws were born in the same year. The Nuremberg Laws denied the Jews their citizenship, employment, education, etc. and defined who was and was not a Jew.

Ironically, in 1983, Wald would find out how these laws applied to him. He was teaching and was invited to spend a week with some schools in Frankfurt, Germany. One day, he visited the city hall because he wanted to find out if he could obtain Rosalie’s and his birth certificates. It was a fairly simple process. All he had to do was give the clerk their dates of birth. She returned a few minutes later.

“There I was, Max Wald. Max had been crossed out and Israel had been written over it. My sister, Rosalie, had Sarah written over her name. At that time, all Jewish males were named Israel and Jewish females, Sarah,” Max remarks.

His father, Charles, traveled throughout Germany selling textiles and saw all sorts of atrocities and knew he had to get his family out. He had the right contacts so he was able to secure visas and passage out of Germany.

However, his father disappeared before the family left and was incarcerated in Buchenwald for disobeying an obscure law. He made it out of prison, however, and the family reunited in the United States. Max states that his father never revealed the details about his experiences while a prisoner.

Meanwhile, Max and his mother, Edith, lived with her parents, Hermann and Frieda Jacobs, until November 1938. That was when thugs in uniforms burst into their home and ransacked the house. This was Kristallnacht, “the night of broken glass.” Looking out the window. Max and his family could see book burnings, beatings, looting, killing, and arrests. In 1939, Rosalie was born.

Max, his mother and baby sister left Frankfurt and went to Hamburg and from there sailed to the U.S. in Nov. 1939. His grandparents didn’t go with them because, although they were aware of the persecution of the Jews, their families had lived in Germany for over 200 years.

“Who would possibly harm them? Besides, Opa (Grandfather) Hermann had served with distinction in the German army,” Max remarks.

By the time they realized that they weren’t safe, it was too late for them to get out. Frieda and Hermann were sent to concentration camps. So were his four aunts. His grandfather and three of his aunts died before liberation, but one of his aunts survived. His grandmother, Frieda, made it out also having spent time in three different camps−Theresienstadt, Bergen Belsen, and finally Auschwitz. She eventually came to live with the family in the United States.

But, coming to a free country did not erase the scars of what the family had endured in Nazi Germany. “Two emotions were always with my parents and later with me- guilt and worry. Throughout the war years, thoughts of people left behind were always present. Worry about what was happening to them and guilt that we were here and were safe and they were in danger.”

When his grandmother arrived in the United States, Max described her as “a remarkably happy woman considering what she had experienced.”

He heard stories about the camps of torture, death, horror, and what Frieda had to endure−looking for valuables in the ovens, cleaning ashes, watching people die, never having enough to eat.

Now, even the children and grandchildren are starting to age. That’s why it’s so important to listen to their stories and keep them close to our hearts. Sadly, genocide is still going on all over the world, but we must do whatever we can to stop it. We can’t sit back and be silent like so many “good” Germans did during the Holocaust.

Peter Erlich

Peter Erlich’s mother and grandparents managed to stay “one step ahead” of the Nazis, figuratively speaking. His mother, Reneé, was born in Berlin in 1929. The family lived a comfortable life. Her father, Alexander, worked for the government as an electrical engineer, but in 1935, that all came to a halt when he was fired from his job.

Alexander knew that things would only get worse, so he moved the family to France because he had a job offer in Paris. They had to leave their relatives behind and just about all their possessions because the government was already restricting the Jewish people’s movements. The only way they got out was that they said they were visiting friends in France.

The family lived in Paris until 1940, just a week or so before the Germans took over the city. Then they fled to Lyon, where they “hid in plain sight.” They kept to themselves and didn’t have much to do with their neighbors. In this way, the family was never betrayed by their neighbors, as many Jews were. His grandfather was in the French Underground and was gone for long periods of time. One day, he was ordered to show up at a certain place and he wasn’t sure what it was for. When he showed up, he realized that they were rounding up Jews, but he managed to escape.

They left Lyon and went by train to Menton near Nice on the border of Italy right on the French Riviera. Alexander had a Gentile friend who let them stay in his summer home. Nobody paid attention to the family because the town was being bombed and their neighbors were too busy worrying about themselves.

Peter’s mother barely escaped capture one day. Against her father’s orders, she rode the bus to school instead of walking. Some Nazis boarded the bus, but she had a fake I.D., so they didn’t realize she was Jewish. After that, Renée’s father put her in a Catholic convent, where she stayed until after the war.

Reneé was sixteen when the war ended and not too long after that, the family moved back to Paris. The family found out later that her father had five siblings in Germany who survived the war. Her mother had two brothers also that survived. Several years later, his mother met an American man and came to the U.S. in 1953 to get married.

Peter recalls, “The experience scarred my mom. She still has a lot of anxiety and has trouble with loud noises because of the bombardments. It’s pretty amazing that my mom, despite what she went through, has never harbored hatred toward Germans or toward any group. She has always been very open-minded about anyone she’s ever met.”

“We Americans are very fortunate that we have never experienced anything like what went on in Germany or had our population decimated by war,” Peter concludes.

We are, indeed, fortunate to be living in freedom, with no fear of being persecuted because of our religion or ethnicity. However, we should never take that freedom for granted.