She was the granddaughter of an enslaved person and the great-granddaughter of an enslaver.

Can you imagine trying to fill out a medical questionnaire in today’s world? Hesitating at the word “gender” or “race?” And trying to explain what it felt like to be a man trapped in a woman’s body? And trying to describe that you were more than half white, yet you were also a good part Negro and 1/8 Native American (Cherokee)?

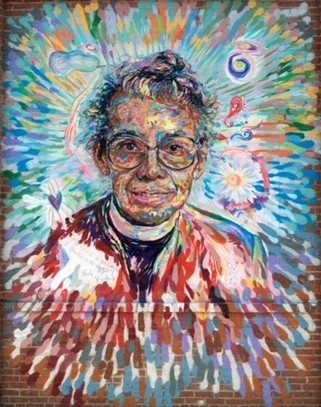

Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray struggled with many of those questions. However, she was definitely a trailblazer, often ahead of her time, and fought for equality, civil rights, and women’s rights. She is the 11th historic woman honored in the American Women’s Quarter Series; her quarter was issued on January 2, 2024.

Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on November 20, 1910. She came from a family of educators. Her aunts and an uncle were all teachers. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a teacher and then a school principal.

In 1914, a four-year-old Pauline Murray went to Durham, North Carolina, to live with her family following her mother’s death. Her father was left a widower with six children, including Pauline, all under the age of ten. He soon couldn’t even take care of himself and became impoverished, grief-stricken, and ill. In 1923, he was beaten to death by a white guard while receiving treatment at a mental institution.

Pauline, who is now an orphan, had an aunt and a grandmother raise her. She had few memories of her parents. However, family members stepped up. They provided reminisces, told stories, and helped fill in the blanks. This information was vital and used later as Pauline searched for her family roots and wrote a book about her life called “Proud Shoes.”

Pauline was ambitious and eager to learn. She finished high school three years early with an impressive resume as editor of the school paper, president of the literary society, class secretary, member of the debate club, forward on the basketball team, and honor student.

She moved to New York City at age 16 to live with a cousin. During the Depression, she waited on tables and saved enough money to attend a public university there, Hunter College. She graduated in 1933 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English.

In 1928, Pauline changed her first name to Pauli and spent several years on a quest for medical assistance with gender. In most cases, she was denied help or hormone treatments. She had a brief marriage but had it annulled. She preferred women as partners and had several relationships in her lifetime, herself taking on the masculine role of the couple. She cut her hair short and preferred pants to dresses. In retrospect, some scholars refer to Pauli Murray as transgender and use both he/she pronouns when describing her.

Two decades before the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Pauli opposed discrimination and segregation. In 1938, she applied for admission to the “all-white” University of North Carolina but was rejected. In 1940, she was arrested for sitting in the “whites only“ section of a Virginia bus. She also helped organize sit-ins in Washington, D.C. and encouraged classmates to go south to support others in the civil rights movement. Her experiences with discrimination steered her toward a career as a civil rights lawyer.

In 1944, Pauli Murray graduated from Howard University in Washington DC at the top of her class and the only woman. In her lifetime, she earned five college degrees (including one from Yale) and received ten honorary degrees.

She applied to Harvard Law School for postgraduate studies but was rejected because of her gender. In 1944, she sued for discrimination and started an extensive letter-writing campaign. It caused the school and faculty embarrassment, if nothing else. Finally, in 1950, Harvard Law admitted women for the first time.

While serving in private law practice, Murray wrote a book called “State Laws on Race and Color. “ Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall called it the “bible” of the civil rights movement. This lengthy publication contains laws and rules that were applied to people of color during the 1950s, and it covers major cities and 48 states.

In 1960, she traveled to Ghana to teach law and explore their African cultural roots. President John F. Kennedy appointed Murray to his Committee on Political and Civil Rights. She worked closely with the other activists, including Dr. Martin Luther King, but felt her opinions weren’t taken seriously because she was a woman.

In 1965, she could put the title “Doctor” in front of her name. She was the first African-American to receive a Doctor of Judicial Science from Yale Law School, and in 1966, she was one of the twelve founders of the National Organization of Women (NOW).

From 1968-1973, Dr. Murray taught at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. Her partner of twenty years, Renee Barlow, passed away in 1973 from a brain tumor. Although they had not lived together, Barlow was considered her closest personal friend for two decades. While working through her grief, Murray sought comfort in her Christian faith and enrolled in seminary.

In 1976, Dr. Pauli Murray could also put the title “Reverend” before her name. She graduated cum laude with a Master of Divinity from the General Theological Seminary in New York City and, a year later, became the first black woman to be an Episcopal priest at the age of 66.

She spent her later years as a public speaker and came full circle back to Baltimore, Maryland, the city of her birth. Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray passed away from pancreatic cancer on July 1, 1985, at the age of 74.

Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray rubbed shoulders with many famous people, including Eleanor Roosevelt. Their chance meeting turned into a twenty-year friendship and lengthy correspondence. Murray later donated fifty of their letters to the Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park.

Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray leaves behind a wealth of written words, including legal guides, books of poems, two memoirs, and collections of sermons and speeches. It’s said she saved everything with a sense of history in mind. She even made tapes of meetings. A final memoir of hers was published posthumously in 1987, called “Song in a Weary Throat.”

Many authors have since written their own accounts of Murray to explain this complex, accomplished, and outspoken woman ahead of her time.

In 2018, the Episcopal Church made Murray a permanent part of their calendar of saints. She is commemorated with a feast day on July 1st.

On her American Women Series quarter, you’ll see the word HOPE in large letters. Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray believed that society can reform when rooted in hope.

“As an American, I inherit the magnificent tradition of an endless march toward freedom and toward the dignity of all mankind,” wrote Pauli Murray in 1945.

![IMG_8870 [Photo courtesy of Schlesinger Library/Radcliffe Institute/Harvard University]](https://www.hernandosun.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IMG_8870.jpg)