Their husbands told them to “stay out of it,” but they didn’t listen. At times, they even felt like undercover operatives. This group of local women was a determined bunch. They demanded better schools for Hernando County and raised awareness in an interesting way in 1947.

Most of the women were well-known. You’ll recognize some of their last names if you grew up in Brooksville. The ladies belonged to Hernando County clubs and civic organizations. Some were club presidents or officers. Some were also wives of civic leaders or spouses of well-known businessmen and farmers.

The group consisted of:

• Mrs. Gus Schultz of the Brooksville PTA

• Mrs. E.T. Mountain of the Spring Lake PTA

• Mrs. J.C. Bacon of the local American Legion

• Mrs. J. T. Daniels, of Spring Lake

• Mrs. Frank Stenholm of the Brooksville PTA

• Miss Mary Belle Rogers, Jr. Service League

• Mrs. John Law of Brooksville Women’s Club

• and Mrs. W.E. Davis, of the Jr. Service League.

In their opinion, Hernando County schools had been neglected for years and it was high time to make things right. They had tried to be polite about it but were tired after years of inaction and double talk.

Where were the schools of nearly a century ago? In the 1930s and 1940s, there were public schools such as Brooksville High, Brooksville Elementary, Moton School, and Spring Lake School. There were also other schools (mainly one-room classrooms) scattered about Hernando County in small communities like Istachatta, Nobleton, Lake Lindsey, Hebron, Masaryktown, and Garden Grove. They had been established to fill the educational gap for youngsters in rural communities, for those who lived too far away from Brooksville.

However, none of the Hernando County schools received adequate funding to keep up with the demands. Each year, they were falling deeper into debt, borrowing against next year’s budget just to pay teachers’ salaries or keep the lights on. And they were paying interest on loans, too, so debt increased with each passing year. Meanwhile, school buildings were in need of serious repairs. They needed everything—equipment, supplies, furnishings and various plumbing and electrical work just for starters.

Yet, there was money to be had thanks to legislation created during the Great Depression. In 1931, the Florida State Racing Commission legalized gambling, and as a result, the state of Florida earned revenue from taxes paid by the winners.

Each dog track, horse track, or jai alai fronton brought in taxable revenue. The legislature declared that half of all tax profits would be passed on and split equally among Florida’s counties. At first, it wasn’t a great amount of money, but as the years went on, it became a noticeable sum.

In 1931, the first year of legalized gambling, the Hernando County government received $9,000 from race track revenue. By the end of the 1930s, the county was averaging $19,000 annually from race track betting and in the early 1940s, it was averaging $30,000. In 1946, Hernando County recorded an all-time high of $98,000 from race track revenue for a single year. In 1947, it was scheduled to exceed that total and was showing $75,000 by mid-year.

Back in 1945, there had been a compromise of sorts. Legislation was passed to give Hernando County schools a small portion of race track funds. It had taken decision-makers almost 15 years to give some of that windfall to schools. They allocated $11,000 in 1945 and another $11,000 in 1946. (The designated fund amount was based on one-third of the annual guarantee of $33,000 in race track money for Hernando County.)

However, funds were now coming in at a much higher rate than the annual guarantee. The Brooksville women could do the math and felt they were being shortchanged. Other counties (Hillsborough, for example) turned over 100 percent of its race track funds to education and our neighbor, Citrus County, gave 40 percent away to schools. Race track funds in Hernando County amounted to $98,000 for 1946, yet they allocated less than 10 percent of it towards schools!

Between 1931 and 1947, Hernando County had received over $500,000 in race track revenue.

Yet the schools had received only $22,000! In early 1947, the women‘s group began circulating a petition for better schools and requested more money. They worked hard and gathered more than 1600 signatures, which represented more than half of the current number of registered voters!

In April 1947, the women’s group copied another county’s plan to improve schools. They contacted reporter Jim Killingsworth of the Tampa Tribune. His thorough investigation and subsequent newspaper articles provided an embarrassing look at the deterioration of Hernando County schools.

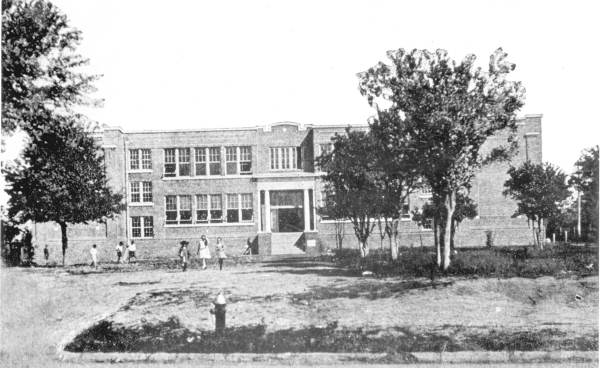

Three schools were visited and evaluated. They were Brooksville High (now known as Hernando High), Brooksville Elementary, and Spring Lake School. It was noted that all schools had similar issues. They had broken ceiling plaster, holes in the walls, broken or cracked windows, damaged equipment, old desks, inadequate lighting, poor heat, and inadequate plumbing. They had broken toilets, escaping sewer gas, and leaky showers.

Brooksville Elementary’s basement was a firetrap. It was filled with old wooden crates, broken desks, and cans of oil. Some rooms and hallways had missing fire extinguishers and no fire hoses. In other locations, the hoses were there but useless, having visible gaping holes. The newspaper stories (complete with photos) brought public attention to 20 years of neglect in Hernando County schools.

The women’s group wanted the county commissioners to support their much-needed school legislation. They didn’t want to blindside them and were open about petitioning for new legislation to help schools. They requested that one-half of Hernando’s future race track revenue be set aside for school improvements.

Something just wasn’t right about the present Hernando County budget. Money was allocated to improve roads and bridges at four times the rate of school funds.

On April 21, 1947, the women’s group went a step further. They called in students to come downtown for a permitted parade. The ladies had worked it out with teachers to have the event occur during regular physical education periods so no classes were missed.

A total of 185 individuals gathered, everyone from teachers to students. Band members marched and played their instruments while others carried placards saying, “We want better schools in Hernando County!” They went twice around the courthouse block.

Meanwhile, the county commissioners were inside at their regular meeting. Can you imagine what they thought when they heard music playing? Or what happened as onlookers poked their heads out of courthouse windows? After two laps, the parade dispersed and spokeswoman Mrs. Gus Schultz of the Brooksville PTA went in to address county commissioners. If she expected a rousing welcome, she must have been sadly mistaken. Only one member out of the four commissioners was actively in favor of the race track legislation.

A Brooksville committee later presented their petition and its signatures to Florida Representative G. Kent Williams. Committee delegates present were W. L. McGee, a service station operator, Miss Mary Belle Rogers from the Junior Service League, and Mrs. W. E. Davis, Vice President of the Brooksville Women’s Club.

By May 1947, Representative Williams told the committee he would introduce the bill they wanted. He would propose that 50 percent of annual race track money be allocated for better Hernando County schools. Florida Senator W.B. Moon said he would back it.

In June 1947, the Senate passed the school aid bill. Florida’s Governor Millard Caldwell signed it into law. The “women’s bill,” as it was called, would make a tremendous difference in Hernando County schools. Many were glad that a group of strong women didn’t sit on the sidelines and “stay out of it.”

![Members of the 1947 State of Florida Senate. [Photo credit: State Archives of Florida]](https://www.hernandosun.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/image0-19.jpeg)

[Photo credit: State Archives of Florida]