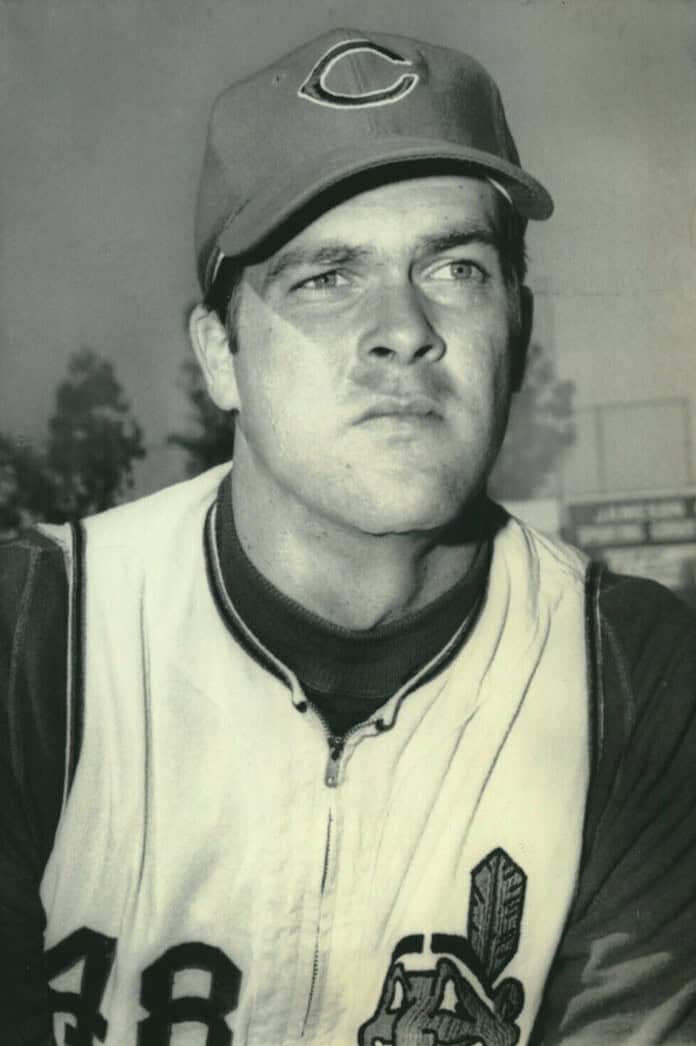

In baseball lore, he is remembered as “Sudden Sam” — perhaps the first Major League pitcher whose fastball topped 100 miles per hour. But in the real world, Sam McDowell has a different nickname.

These days, he is “Sober Sam” and that title is part of a lasting legacy that goes far beyond anything McDowell ever did on the baseball field. He’s the guy who, across five decades, has helped hundreds (maybe even thousands) of Major League Baseball players stay clear of the problems he once had with alcohol.

McDowell is 82 now and he lives in The Villages. His story is that of a rocket-like ride to the top of the world, a slow and devastating crash and — most of all — a spectacular redemption.

“I’ve never had a bad day,” McDowell said in a phone interview earlier this week. “If I hadn’t gone through what I went through, I wouldn’t be where I’m at today.”

Where McDowell will be on Saturday is at the Spring Hill Showcase Sports Card and Memorabilia Show at St. Joan of Arc Catholic Church Parish Hall (13845 Spring Hill Drive). He’ll be signing autographs and selling copies of his autobiography “The Saga of Sudden Sam: The Rise, Fall and Redemption of Sam McDowell.” But there’s more to it than that.

When McDowell appears at these card shows — and that doesn’t happen very often — he engages with the audience. He’ll talk mostly about his baseball days and what it was like to pitch against Mickey Mantle or strike out Roberto Clemente in an All-Star Game. If he’s asked, he’ll talk about his addiction, recovery and all that’s happened to him since he last put on a Major League uniform for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1975. McDowell’s life is an open book and no topic is off limits.

“I have no regrets,” said McDowell, who is scheduled to sign autographs from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Saturday. The show will continue Sunday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. and McDowell said he may do an encore appearance depending on how he feels after Saturday’s session.

McDowell’s story runs deep and the best way to run through it might be to start back in 1960. This was before Major League Baseball started holding a draft, but every team was well aware of the 6-foot-6 left-hander with a blazing fastball. In his senior season at Pittsburgh Central Catholic, McDowell went 8-0 and struck out a whopping 152 batters in 63 innings. McDowell was widely viewed as the No. 1 prospect in the nation. Right after graduation and during his third appearance on the popular television show “To Tell The Truth,” McDowell announced he was signing with the Cleveland Indians (now the Cleveland Guardians). Cleveland handed McDowell a $70,000 signing bonus — a small fortune by Major League Baseball standards in those days.

McDowell and his father asked the Cleveland officials for a normal progression through the minor-league system and the first assignment was with the Class D team in Lakeland. But McDowell’s progression ended up being anything but normal. He was quickly promoted to the Triple-A team in Salt Lake City. Although he wasn’t in Utah for long, that’s where one of the most remarkable and underreported incidents of McDowell’s career took place. He cracked two ribs while throwing a

pitch.

“Hey, when you’re throwing 103 miles per hour, you’re throwing with everything you have,” McDowell said. “It impacts everything in your body.”

The ribs healed and McDowell pitched well. As September rolled around, McDowell was brought to Cleveland to join the Major League club. A week before his 19th birthday, McDowell made his first Major League start. A couple of years of bouncing between the majors and minors followed. During those years, McDowell didn’t drink at all.

“I was a health nut back then,” McDowell said. “I was obsessive-compulsive about my health.”

It wasn’t until 1964 that McDowell was in the big leagues to stay and it was around that time that alcohol entered his life and, soon after, took it over.

“I had a game where I pitched well and a couple of the veteran players asked me to join them for dinner,” McDowell said. “One of them ordered a scotch on the rocks. So, I ordered a scotch on the rocks. Another guy ordered something else, so I ordered something else. So, I started drinking — a lot. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was born an alcoholic. It’s a disease that you’re born with and there was a lot of it in my family.”

Still, McDowell had his fastball and there were moments of brilliance early in a career that eventually included six appearances in the All-Star Game and five American League strikeout titles. He posted a career-high 325 strikeouts in 1965 and won a career-high 20 games in 1970. On the cover of its May 23, 1966 edition, Sports Illustrated ran a photo of McDowell with the caption “Faster than Koufax?”, a reference to Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax, considered by many to be the best left-handed pitcher in history.

McDowell’s only issues were control problems — on the mound and off it. As a pitcher, he sometimes struggled to find the strike zone. He led the American League in walks five times and wild pitches three times. As a person, McDowell struggled to control his drinking.

“I was only pitching once every four days,” McDowell said. “I would drink after a game I pitched and for the next two days. But I wouldn’t drink the day before I pitched and I would always work out that day. I assumed I was sober on game days. But I later realized I wasn’t. Alcohol affects your brain for much longer than one day. I think there were points where I knew I had a problem, but I was escaping by drinking. I medicated myself by drinking more and it kept getting worse.”

The drinking took a toll on McDowell’s pitching and Cleveland management viewed him as a problem child. A year after he was chosen as the American League’s 1970 Pitcher of the Year, McDowell’s record dropped to 13-17 and he walked 153 batters.

“It’s sad because, without the alcohol, Sam could have been one of the best pitchers ever,” said former Detroit Tigers pitcher Denny McLain, a two-time Cy Young Award winner and a close McDowell friend. “Sam was throwing 100 miles per hour before anyone else. He could have been the left-handed Nolan

Ryan.”

Cleveland traded McDowell to the San Francisco Giants and the 1972 season and the early part of the 1973 season weren’t pretty. In June of 1973, the Giants made a cash deal with the New York Yankees for the rights to McDowell. Things didn’t get any better in New York.

At the end of the 1974 season, McDowell was out of a job. In a last-ditch effort to rescue his career, McDowell called his hometown Pittsburgh Pirates and pleaded for a chance. Pittsburgh’s general manager told McDowell what most people in the baseball world already knew all too well.

“He said, ‘You have a drinking problem,’” McDowell said. “The best he could offer was to let me come to spring training without a contract and see if I could make the team.”

McDowell didn’t drink that spring and the Pirates put him in their bullpen as the 1975 season started. But the end of the road came when McDowell went out drinking one night after pitching well. He showed up drunk at the ballpark the next day. The Pirates said no more and so did the rest of the baseball world.

McDowell started selling insurance and said he was good at it. But he was drinking constantly by that point. His wife took the children and left him. One day, McDowell’s boss came to him and told him he’d had enough. McDowell moved in with his parents in Pittsburgh. It was in their kitchen at 3 a.m. one morning that McDowell said he had some sort of breakdown that eventually would lead to a dramatic turn for the better.

He checked into Gateway, a rehabilitation facility near Pittsburgh. McDowell spent 30 days there and his world got a little brighter. There was time for lots of introspection and McDowell listened closely to his counselors as well as the other patients. When he left Gateway, McDowell had an understanding of his problems, but he wanted to know more about alcoholism and he enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh, where he earned an associate’s degree in sports psychology and addiction counseling. McDowell also attended numerous workshops throughout the Northeast and became a certified addiction counselor.

“I wanted to learn, ‘Why me?’” McDowell said. “I came to realize it wasn’t some sort of character flaw like a lot of people thought back in those days. Alcoholism is a disease.”

After getting sober, McDowell was invited to pitch in an old-timers game in Jacksonville. Several major league scouts were there and clocked his fastball in the upper 90s. The possibility of a return to baseball was mentioned. McDowell quickly said no. He had something else in mind and that would shape the rest of his life.

“I wanted to help others,” McDowell said.

The Texas Rangers had heard about McDowell’s recovery and asked him to come on board as an addiction counselor. That worked so well that the Toronto Blue Jays wanted to adopt McDowell’s program and the Rangers agreed to share his services. Other teams heard about his success. Eventually, Major League Baseball made McDowell a consultant for its Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) and he began doing some counseling for the Major League Baseball Alumni Association.

These days, McDowell likes to talk about numbers. But not the 100 mph fastball that once was his trademark.

“My program has had an 85-percent success rate with drugs and alcohol,” McDowell said. “The success rate for society in general is less than 12 percent.”

Along his journey, McDowell’s life has taken many turns for the better. While stopping to ask directions to a dinner in Orlando, McDowell found himself in a K-Mart parking lot. That’s where he met his second wife, Eva. They agreed to meet for coffee after McDowell finished dinner. They’ve been together for the 22 years that followed. They lived first in Clermont before moving to The Villages a little over 10 years ago.

McDowell said he retired four years ago. But he hasn’t stopped working completely. He talks frequently to his son, Tim, who has taken over McDowell’s counseling and consulting roles. Tim is a licensed psychologist and addiction counselor.

“Tim’s better at it than I was,” McDowell said. “He’s enhanced the program and there’s been some crossover with the NFL, the NBA and the NHL.”

McDowell said he still stays in touch with about 70 percent of the athletes he’s counseled. He says his baseball career is part of his story, McDowell said the legacy he’s most proud of is the lives of others that he has helped improve.